The modern world speaks incessantly of the nation while understanding it less and less. The word remains on our lips, but its substance is hollowed out. For some, the nation is reduced to a managerial unit for economic growth or security policy; for others, it becomes a totem of identity, severed from moral responsibility and ordered toward self-assertion alone. Catholic thought, however, refuses both reductions. It insists that the nation is neither an idol nor irrelevant, rather the nation is a moral reality. As such, the nation is a form of shared life shaped by history, culture, sacrifice, and responsibility before God.

A true approach to the nation begins not simply with sovereignty or borders, but with the human person as a social being, created for communion and ordered toward the common good. This starting point is decisive, and it places Catholic reflection at odds with both technocratic globalism and romantic nationalism.

I. The Nation as a Community of Moral Memory

Gaudium et Spes speaks of peoples and nations not as abstract entities, but as communities bound together by the spiritual bonds of Christ forged through time that demands “freedom in what is unsettled and charity in any case.” A nation is not merely a population under a government; it is a people who remember together. Memory here is not nostalgia, but the moral continuity of the inheritance of language, custom, worship, and shared judgments about what is honorable and what is shameful. It is the pedagog, paideia, and shared way of life of a people that is remembered and cherished.

When memory is lost, politics becomes weightless. Laws still exist, but they no longer arise from a people who recognize themselves as responsible for one another. The Magisterium consistently warns that societies which sever themselves from their cultural and religious inheritance do not become neutral; they become vulnerable to domination by ideology, appetite, or power. Their is no spiritual neutrality for the soul of a nation. Either its moral memory becomes baptized and their customs become inculturated by the gospel or it will align itself with the strong gods that have preyed on the gentiles for time immemorial.

The Catholic tradition therefore affirms the legitimacy, even the necessity, of national cultures. As Centesimus Annus observes, the person is always situated within a people, and it is through this mediation that freedom becomes concrete rather than abstract. How could any of the covenants throughout the Old Testament be intelligible apart from such mediation? God loves not simply individuals, but peoples. God desires for the nations to be brought into His family, not simply some of their citizens. This ought to give those who treat the nation as a formality or hangover inhibiting true peace pause. Nations matter. Yet, a nation worthy of love is one that hands on more than material prosperity: it transmits meaning. Not any meaning, but the truth.

II. Love of Country and the Order of Charity

The Church has never opposed love of one’s country. Patriotism remains a virtue and who can fail to admire a person who has served their country without suppressing the most innate feelings of pathos. What the Church has firmly opposed is the deformation of such affection and devotion. Properly understood, patriotism is an expression of the ordo amoris, the ordered love by which we give ourselves first to those nearest to us without denying our obligations to the whole complex web of humanity, and, in Christ, the human family.

This point is often missed in contemporary debates. Universal charity does not erase particular loves; it purifies them. As Fratelli Tutti insists, openness to all peoples presupposes rootedness somewhere. Deracination obscures the dignity of the other by confusing the natural order of love for oneself. A love that claims to embrace everyone but is responsible for no one in particular is not charity but sentimentality.

The nation, then, is a school of love. It teaches us how to care for people we do not personally know but to whom we are bound by shared life. Taxes, laws, military service, public institutions, these are not merely technical arrangements. They are moral practices that habituate us either to solidarity or to resentment, depending on whether they are ordered to the common good. We have been living through the great hallowing of such practices. Subsequently we are living in a very contentious time because the very soul of the nature is obscured through virtue of nobody being able to agree on how the nation’s body truly is or was.

III. Against the False Absolutes of Modern Politics

The Magisterium’s teaching on nations consistently rejects two false absolutes. The first is statist nationalism, which treats the nation-state as the highest moral authority tout court. This temptation is perennial, and the twentieth century provided devastating examples of what happens when national power is unmoored from transcendent truth. When the state claims total loyalty, it inevitably suppresses the Church, the family, and any mediating institution that reminds it of limits.

The second is homogenizing globalism, which dissolves nations into administrative regions governed by economic or bureaucratic logic alone. Caritas in Veritate warns that such an approach undermines authentic development by ignoring the cultural and moral dimensions of human life. A world without nations is not a world of peace, but a world in which persons are stripped of the communities that give them voice and protection.

Catholic teaching insists instead on subsidiarity and solidarity together. Nations matter because they are the level at which shared responsibility can still be intelligible. They are large enough to pursue justice and small enough to sustain loyalty.

IV. The Political Vocation of a People

A nation is not merely something we inherit; it is something we are called to steward. We owe our nation something. The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church emphasizes that peoples, like persons, have a vocation. This vocation is not defined by domination or exceptionalism, but by service to the common good. Such service ought to be wholeheartedly embraced internally and in relation to other nations.

Here the example of historically Catholic peoples is instructive, not because they were without sin, but because they understood that national life stands under judgment. Feasts, fasts, patron saints, public acts of repentance: these were ways of acknowledging that a people, too, must give an account. Modern secular politics, by contrast, knows only success or failure, not guilt or responsibility. This has encouraged each new “regime” elected to office every four years, executively speaking, to quickly shake off any pretense of restraint and to break as many things as quickly as possible in favor of the political actions they have deemed necessary to their cause. All precedent of custom and decorum are anathema in the face of such unrestrained ambition. Recovering a true approach to the nation requires recovering a sense of corporate moral agency. Nations can sin. Nations can repent. Nations can reform their laws to better reflect justice. Without this grammar, political life collapses into endless power struggles without the possibility of conversion.

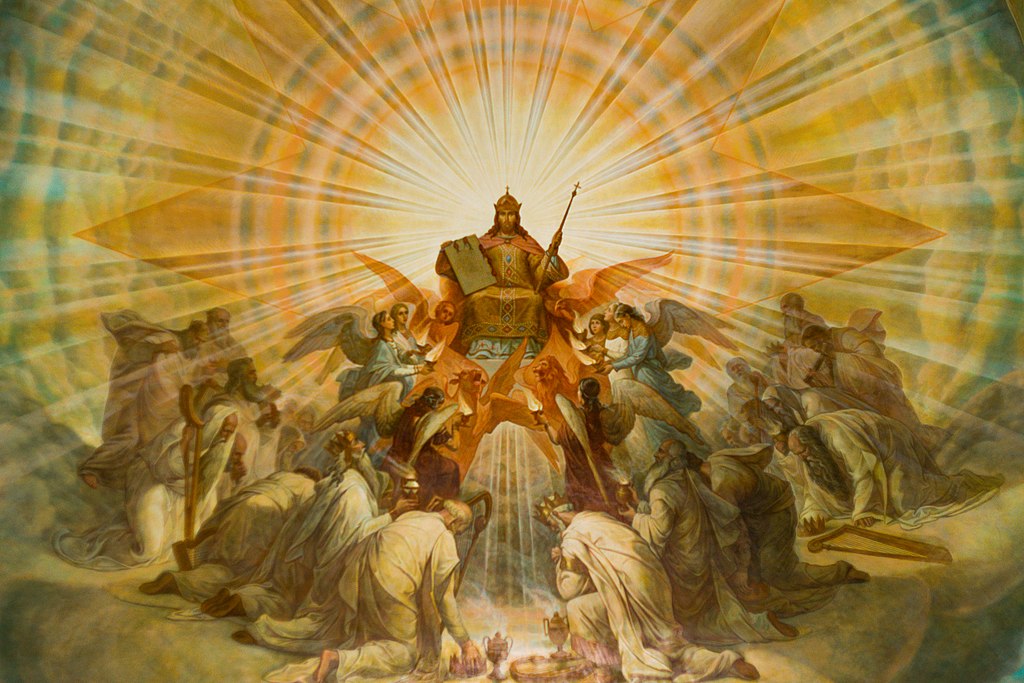

V. Christianity Does Not Abolish the Nation—It Transfigures It

The Church is universal, but she is never abstract. She takes flesh in particular places, among particular peoples. Pentecost did not erase languages; it sanctified them. This is why the Magisterium repeatedly affirms the right of peoples to preserve their cultural and religious heritage while opening themselves to communion with others.

A nation shaped (even imperfectly) by Christian anthropology understands that its purpose is not self- glorification but the flourishing of persons made in the image of God. It is true, as Tolkien said, that history for us is a long defeat. We shouldn’t be surprised when nations, like all things here below, return to dust as a testament to the truth of the opening lines of Ecclesiastes. Nonetheless, nations have a purpose and a grave responsibility to promote and steward flourishing. Its laws protect life because life is sacred, not merely because it is useful. Its economic structures respect labor because work participates in creation. Labor is a good in and of itself worth care and attention. Its borders exist not as walls of exclusion, but as the conditions under which hospitality can be responsibly offered.

Such a nation will always be unfinished. But it will be intelligible. It will know what it is for.

Conclusion: Recovering the Moral Imagination of Nationhood

The crisis of the nation today is not primarily institutional; it is imaginative. We no longer know how to think about national life in moral terms. Catholic social teaching does not give us a program or a platform, but it gives us something more necessary: a way of seeing. To approach the nation truly is to see it as a community of responsibility, bound by memory, ordered by love, and accountable to a truth higher than itself. Anything less will either collapse into coercion or dissolve into meaninglessness. The task before us is not to invent a new nation, but to recover the moral depth of the one we have received, the United States of America, and to hand it on, chastened and purified, to those who come after us.