What draws many Americans today toward nationalism, and, more uncomfortably, toward racialized accounts of belonging is not first ideology but bereavement. The contemporary American, whether they recognize it or not, is filled with sorrow. There is a thick grief hanging over the American imagination like smog. Something has been taken from them, or perhaps, more precisely, something was never truly given. They sense the absence of a peoplehood that endures through time, a culture capable of remembering its dead and preparing its unborn for a shared life. In place of this inheritance, they were handed products, spectacles, and identities designed for consumption rather than transmission.

The result is a strange condition: Americans possess affections without memory, loyalties without lineage, and symbols without substance. People have a stronger emotional connection to Mountain Dew (and the other major brands and IPs that have followed them throughout childhood) than their great grandfather. They do not feel themselves to be a people, yet they ache for belonging. Nationalism and race realism arise here not primarily as doctrines slavishly followed out of stupidity or alternative scientific gurus, but as attempts to recover density. The thinness of American culture leads to a visceral desire to reattach political life to something older, thicker, and more resistant to liquidation than the global market, Disney+, or the administrative state. If one’s place in the world only belongs to a person as much as a subscription service it is truly a sad state of affairs.

I. The Collapse of Cultural Memory

Cultural memory is not the same as nostalgia. We are inundated with nostalgia. No, memory is much more human. Memory is an act of responsibility toward the dead and the unborn; it binds generations together in a shared moral horizon. As Ratzinger often emphasized, a society without memory becomes manipulable, because it no longer knows who it is or what it owes. Memory anchors freedom in truth. In fact, when we look at salvation history, memory is what preserves justice and religious ritual and action in a people. The Israelites must remember what God has done for them and a Catholic at every mass must “do this in memory of Me.”

America, however, has undergone not merely forgetfulness but systematic amnesia. Its institutions (educational, economic, and cultural) have largely abandoned the task of handing down a way of life. Even the actual complex origins of our country are forgotten in favor of grand sweeping narratives that easily lend themselves toward the current “way things are” in Washington since that goes by many names. Everything is now marketing. Even the presidency has devolved into a WWE spectacle rather than a substantive act of service to the American people. Cabinet picks are more like public declarations of co-looters instead of fellow servants. This is collapse of civil service and responsibility of place.

Instead of apprenticeship in virtue, citizens are offered credentials and credentialism. Instead of initiation into a people, they are offered identities that can be adopted and discarded like consumer brands, mostly because they are consumer brands that will be abandoned as soon as they are no longer expedient.

The old mediating structures of churches, neighborhoods, extended families, and guild-like professions were not perfect, but they did something irreplaceable: they connected individuals to a story larger than themselves. Also, and this is important, they were “natural” not that they just simply happen without any action on the part of persons but in the sense of not violating the natural law (often arising from it) and human dignity in their manners of operating (at least in principle, if not in practice). Their erosion has left Americans suspended in what might be called perpetual presentism, unable to situate themselves within a meaningful past or a credible future. This experience of narrative drift is the most deflating and despairing experience a people can find themselves within.

II. Globalization and the Logic of the Disposable

The ideology of allegedly “neutral” globalization did not merely integrate markets; it redefined value itself. What cannot be optimized, scaled, or monetized is treated as irrational sentiment. Local cultures, ancestral memory, and regional loyalties are tolerated only as aesthetic curiosities or lifestyle choices, not as authoritative sources of meaning meant to be honored and patiently listened to. It’s cute to love where you are from, but it’s not respected. It might even have a market, but it shouldn’t really occupy your memory.

This logic is deeply anti generational. Products are not designed to last. Careers are no longer vocations but sequences of transactions. Communities are temporary to match the expansion of the mercantile mind over every facet of human life. This is the great gift of liberal freedom. Even identities are consumable. The market does not hate tradition; it simply finds it inefficient. The market doesn’t care for it.

Pope Francis has called this a throwaway culture, but the phrase risks understatement. What has been discarded is not merely things, but the idea that human life unfolds across generations with obligations that cannot be priced. Obligations don’t imply stagnation, but they do imply a genuine sense of piety, which can be complex. A society formed as a throwaway culture cannot sustain a people or a place. It can only manage a population and extract resources.

III. Why Nationalism and Race Realism Appear Plausible

It is within this vacuum that nationalism reemerges, but in a unique post-liberal form. This strong god is re-emerging in new garb. Often, as we can all see, the internet is particularly suited for its re-emergence in the most distorted forms. For some, the nation appears as the last remaining structure capable of resisting global abstraction. For others, race becomes a surrogate for memory—a biological shortcut to permanence when cultural inheritance has failed.

These impulses are not wholly irrational. Admittedly many promoters, explicit and implicit, of such views have a much more dynamic, and somewhat historically sober points. They reflect a correct intuition: belonging must be concrete, embodied, and historically continuous. It is not simply irrelevant where you are from or what you are about or what you worship. True, in the scandalous particularity of Christ there is neither Jew nor Greek. Yet it is precisely in Him that this is the case. The problem is not that people desire rootedness; it is that, having been denied real inheritance, they grasp at substitutes that promise solidity without moral formation (and oftentimes coherence).

Race realism, in particular, exploits the longing for permanence while evacuating it of ethical responsibility and absolutizing certain contingencies apart from other truths necessary to preserve the Christian concept of human dignity. It seems to offer identity without the hard work of vocation, ancestry without accountability, and continuity without love. Christianity cannot accept this reduction, not because it denies difference, but because it understands difference as personal and relational, not deterministic. A people is formed through shared life, sacrifice, worship, and law, not merely through blood.

Race realism, to older generates appears as an immature movement. This might be true. But it is also these same qualities of Christianity that tells the lie of Rawlsian Liberalism which presents itself as the mature solution to the chaos of modern pluralism. Once again, a people is formed through shared life, sacrifice, worship, and law. The truth of these qualities is rooted in the natural law, reason, and revelation unto the fruit of integral human development.

IV. Phantom Affections and the Failure of Transmission

American culture has trained its citizens to love things that could not love them back. Brands replaced rituals. There is a greater catharsis in the family Dairy Queen run then the Easter Vigil. Entertainment replaced festivals. One is more likely to watch hundreds of hours of streaming then to put in the work necessary for a truly communal event. Political slogans replaced creeds. How many people know the phrases of the day (“Make America Healthy (Great) Again,” “America First,” “No More Kings,” “Deny, Defend, Depose”) but don’t know their own Christian creeds.

What we have grown to prefer is ephemeral. These objects of affection were never meant to endure, and they were never meant to be passed on. Who possibly cares about the slogans of yesteryear “Yes We Can” or even the attempt of the current administration of spending copious amounts of energy re-branding things like the Gulf of America or the Department of War. Yawn.

As a result, Americans feel loyalty intensely but incoherently. They have marketed into a frenzy like what bugs fighting above the deep (that they perhaps dont even perceive). They argue fiercely over symbols that lack real thickness because the difficult work of building institutions for grandchildren rooted in the way things actually are was never done. You cannot passively preserve the human inheritance in which you have the obligation to pass on to your children, your community, your church, and your nation. You have to intentionally work for it throughout your entire life and slogans won’t preserve and encourage such a toil.

Instead of becoming something to preserve the stability of one’s own local region, becoming interwoven in the shared life of a place, we have chosen (or been pushed into) jobs like mercenaries. Universities became credential factories. Corporations became rootless. Churches often mirrored therapeutic individualism and aped globalist place-less language of a vapid universalism devoid of Catholicism’s sui generis ability to preserve particulars without absolutizing universals into an oppressive ideology. Politics became spectacle. Families became unfamiliar with children spending most of their time at school, at sports, and online while mom and dad both are at work, or socializing, or online.

The tragedy is not simply cultural decline; it is moral disinheritance. A generation was taught to consume rather than to steward, to express rather than to receive, to disrupt rather than to build. Often they weren’t even given the chance to do otherwise because the goal of their parents, teachers, and government was to raise global citizens not excellent St. Louisians, Nebraskans, or even Midwesterners. To be local was to be behind. When such a generation awakens to the emptiness of this arrangement, it is unsurprising that it seeks refuge in harder, older forms of belonging, even if those forms are misshapen. Sow the wind and reap the whirlwind.

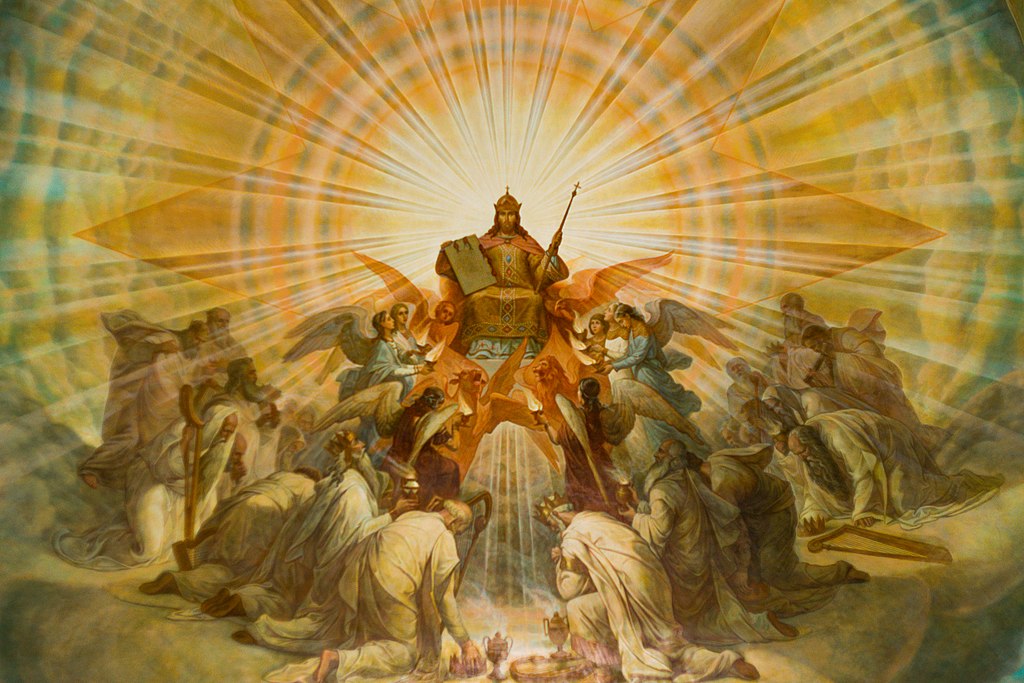

V. A Christian Account of Memory and Nation

Christianity offers neither commodified identity nor racial myth, but a memory that is thicker than blood and more enduring than markets. The Church remembers in a way the modern world cannot: she remembers martyrs, saints, sins, and reconciliations. She remembers in the living communion of her saints. The triumphant in heaven, the penitent at heaven’s door, the militant on this earth and all the potential, diverse members of her body. She has always been destined to baptize all the nations. Her purpose is universal and Her power from on high has the means of such an endeavor. She binds past, present, and future in sacrament and story.

Here Vladimir Soloviev’s insight is decisive: true unity does not abolish difference but draws it into a higher harmony under Christ. Cultural memory, rightly ordered, is not self-enclosed. It is open to purification, repentance, and growth. The traditions of men, when kept in the light of the Son do not need to fester in disorder or half-truths but can be purified and indeed healed into their potential. The Church does not erase peoples; she teaches them how to remember truthfully and live fully alive.

A Christian politics of memory, of the real, can provide America what it desperately needs. Together we can rebuild institutions that transmit virtue, not merely skills. Together we can honor our ancestors not as idols, but as teachers with the fondness of piety whose failures and achievements instruct us. When they teach truth and goodness we receive it gratefully; when they teach sin we reject it but in piety of covering their nakedness. Together we can recover the notion of inheritance as obligation, not entitlement.

Together we can refuse the lie that neutrality is possible in cultural formation. Together we must insist that economic life must serve generational stability, not perpetual disruption. Or we can continue down the road we are on toward the complete demoralization and destruction of whatever is true, good, and beautiful of the American experiment.

VI. Toward a People Again

Americans do not need a stronger aesthetic reprising of twentieth century nationalism in new technocratic color. Americans need to become a people capable of remembering and promising. This will generate something to behold, something that is actually captivating instead of artifice. This cannot be achieved by force, nor by ideology, nor by nostalgia. The memes and voting intentionally once every four years will not recover what we lack.

It requires patient reconstruction: families that expect grandchildren, communities that plan beyond election cycles, churches that teach love-suffering rather than mere therapeutic affirmation. It requires urgent sacrifice: men working diligently and consistently towards plans made for this time and place, inter-generational support over the American expectation of coasting in retirement, investing one’s income into one’s community and groups of regional and national interest that build alternative institutions that can withstand the major changes facing us all. Both of these require true virtue and true charity. They won’t come easy, overnight, or passively. We must look to our past to see what is worth preserving and restoring. We must be creative and prudent to figure out what is uniquely needed at this time to do so.

The Kingship of Christ does not flatten national life. Our King gives our nation depth. Under Christ, memory becomes truthful, difference becomes meaningful, and unity becomes something other than coercion or consumption. Only such a vision can heal the phantom affections of Americans generated by years of falsely asserting neutrality and constantly devoting ourselves to consumption. Only such a vision and a reality can turn our affections once again toward loves that endure.

Many refuse to admit the reality we are in, clinging to the post war consensus utopian dreams of a thin liberalism establishing world justice without any roots in higher, more ancient realities. Until then, the temptations of nationalism and race realism will persist—not because they are true, but because they gesture toward a truth that has been abandoned: that a people is not made by markets, memory cannot be mass-produced, and love cannot endure through marketing alone.