William T. Cavanaugh diagnoses, in a manner similar to Reno’s weak/strong god framework, that modern political thought has a false anthropology and a false soteriology. It has an untrue narrative to base its moral decisions upon. The modern nation-state presents itself as the ultimate guardian of peace, order, and salvation, supplanting the Church’s cosmic and communal vision. The liberal market culture reinforces such secular messianism by shaping people as consumers and “private” individuals rather than members of a body ordered toward a shared good. As a result, modern man is fragmented, with a false public liturgy that is ordered to a mode of salvation that can never work and obscures the true spiritual needs of persons.

A Catholic political vision must therefore recognize that human beings are not merely economic consumers or ideological units, bound by appetite (consumption, power, prestige) or coerced by attachments (tribe, identity, party, fear). Rather, they are persons called to integral development (bodily, socially, spiritually, morally) in the order of salvation and redemption.

Integral Human Development

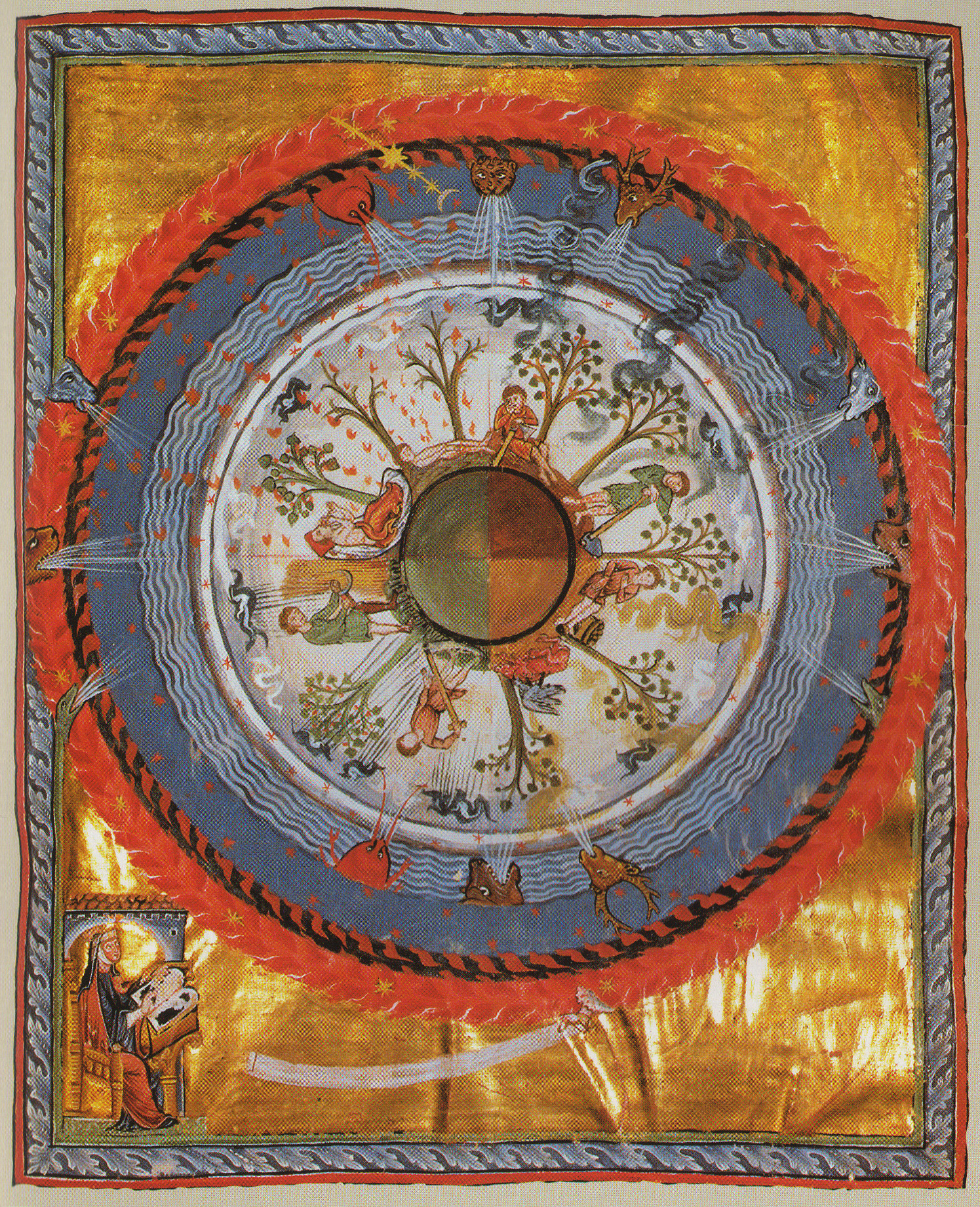

Integral human development means that development is not simply technical or economic, as the normative political discourse suggests, but involves love of God and neighbor, culture, and community in light of Christ. David L. Schindler argues that our institutions, including political and academic ones (what many in neo-reactionary parlance call “the Cathedral”) must be willing to be shaped by a vision of the human good that is not reducible to utility or profit, but is, ultimately, eucharistic.

In this light, a Catholic politics refuses a mere politics of appetite (the state or market simply satisfying desires ad infinitum) or a politics of attachment (which treats persons as solely bound to particular interests, identities, or power blocs). Instead, it invites political structures and civic life to encourage persons to develop (intellectually, morally, spiritually, socially) and to live for the transcendentals (truth, beauty, and goodness) rather than to settle for lesser substitutes.

Thus, Schindler’s approach invites us to re-frame politics as part of the human person’s journey toward the good, rather than as a zero-sum struggle of appetites or a business of attachments. In fact, Schindler’s approach allows us to see every individual’s vocations and interactions in a profoundly personal way. Why? Schindler’s corpus reveals that a proper apprehension of the Christian ordering of nature and grace actually better accounts for the secular activities of man. This is best accounted by Schindler’s preferred image of the baker. In electoral politics, that baker will be mentioned for some strong god’s purposes, perhaps an economic or cultural talking point. For Schindler, the point is simple yet significant: it makes a difference, and it matters in how we conceive of politics, if the baker bakes out of love. The Marian fiat, love as perfectly expressed in creaturely participation in Christ’s mission, transforms the way we can live in this order of history.

A Politics of the Real

Building on the metaphysical foundations of his father, D.C. Schindler’s Politics of the Real (as expressed in his book of the same name, his Freedom from Reality and God and the City) seeks to correct what he sees as the modern political error: the inversion of act and potency, whereby liberalism treats power and rights as abstract possibilities rather than grounded in the actual good. He argues that politics must be ordered to the real good of the community, not simply to managing desires or enforcing attachments (Kant’s society of devils).

For D.C. Schindler, liberalism’s emphasis on autonomy and rights collapses the distinction between what is and what ought to be becoming a politics of the unreal where the nation-state lives off of the imagination of the individual rather than a shared reality jointly apprehended as creatures participating in the transcendentals. A Catholic politics of the real, then, locates authority and community in the common good that precedes politics, not in mere aggregation of interests or capacities to choose.

In terms of appetite and attachment, this means that attachment to politicised identities or appetitive demands must be challenged by the summons to the real: that human beings are made for communion with each other and with God, and that politics should encourage the actualisation of that common good charity makes possible. Rather than politics as appetite-satisfaction or attachment maintenance, we can remember God and get a politics as participation in the real good of the polis oriented toward the transcendent with a real Social Kingship that lays out the full story we ought to have our imaginations infused by.