In the midst of frenzied electoral cycles and ideological posturing, the question of what a truly Catholic politics might look like often gets lost in the clamor over parties, personality, and policy. Yet the Catholic tradition offers far deeper roots than Democrat/Republican, Progressive/Reactionary, Nationalist/Socialist, even classical liberalism itself. In the treasury of our saints and greatest philosophers and theologians, we have reflected upon the gift of God’s revelation and discovered insights into the human person, the common good, and what it means to live in community. Drawing on Anglophone Communio thought, specifically David L. Schindler’s understanding of integral human development, his son D.C. Schindler’s progressive articulation of a “politics of the real,” and Andrew Willard Jones project of thinking through a politics of friendship, we can propose a politics that moves beyond mere appetite or attachment into something more like what the Church’s social teaching calls integral human flourishing.

From Appetite and Attachment to True Flourishing

In the Church’s intellectual tradition, appetite and attachment are central to understanding morality in relation to both nature and grace.

Appetite is an inclination toward the good. Every creature naturally tends toward its own perfection or fulfillment. Yet appetite follows upon cognition: a thing must first be known, in some way, as good before it can be desired. Thus, the proper object of appetite is a good as apprehended.

There is an unconscious natural appetite present in all beings, inclining them toward their proper ends. In animals and humans, this is elevated to a sensitive appetite, which can be divided into the concupiscible (seeking pleasurable or painful goods) and the irascible (striving for arduous goods). Finally, in human beings, the appetite reaches its highest level as an intellectual appetite, which—because we are rational—takes the form of the will, tending toward the good as apprehended by reason.

The point here is that we do not naturally or effortlessly desire what is best. The proper ordering of appetite requires both intellectual and moral effort, as well as the healing aid of grace, since our nature is wounded and burdened by concupiscence.

In the moral order, attachment seems to me to be a closely related concept. Attachment can be rightly ordered or disordered. When rightly ordered, the will adheres to the good in accord with right reason and divine law—ultimately, this means in accord with charity, understood as the love of God above all things. Charity has a narrative form as well: the paschal mystery. This is why Aquinas can state that the cross is not only a remedy for sin but that the passion of Christ is an example that “completely suffices to fashion our lives. Whoever wishes to live perfectly should do nothing but disdain what Christ disdained on the cross and desire what he desired, for the cross exemplifies every virtue.” When attachment is disordered, however, the will clings to created goods in a way that impedes its orientation toward the ultimate good: both the natural desire to see God and, more profoundly, the supernatural participation in Christ’s own love for the world and for souls.

This inordinate affection is among the greatest obstacles to man’s rational comprehension of revelation, his growth in virtue, and even his acknowledgment of truths that seem self-evident. In the economy of grace, rightly ordered attachment is the adhesion of the will to charity. When love becomes fixed when the will or sensitive appetite rests in the good—it produces this kind of attachment.

To love, properly understood, is to will the good of the other as it truly is, not merely as one perceives it to be. This presupposes an order of goods: first, the Supreme Good—God Himself—and second, created goods, which are good only insofar as they participate in or reflect God’s goodness. As Aquinas teaches, virtue consists in the right ordering of the affections. Disordered affections or attachments draw the soul away from God, producing spiritual disorder. The person ruled by such affections experiences a kind of slavery of the soul, for the will cannot find rest when it clings to anything less than God.

We are therefore, for the sake of freedom, called to detachment. This is not indifference or apathy, but rather the freeing of the will from undue adherence to created goods. The detached person loves created things rightly, because their love of God is not hindered by lesser loves. As Aquinas writes (ST II–II, q. 184, a. 3), the perfection of Christian life consists chiefly in charity and, instrumentally, in the counsels and commandments that remove whatever hinders the act of charity.

Detachment creates the interior space necessary for spiritual growth, which unfolds as man freely gives himself to the service of God. “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” says the Lord, not because lack itself is good, but because poverty of spirit is that voluntary humility and detachment from even temporal goods which allows the soul to serve God wholeheartedly in every state of life. Once again, every person, whether bishop, priest, religious, or lay, ought to look toward our Savior’s paschal mystery as the source and example of the mission of their life.

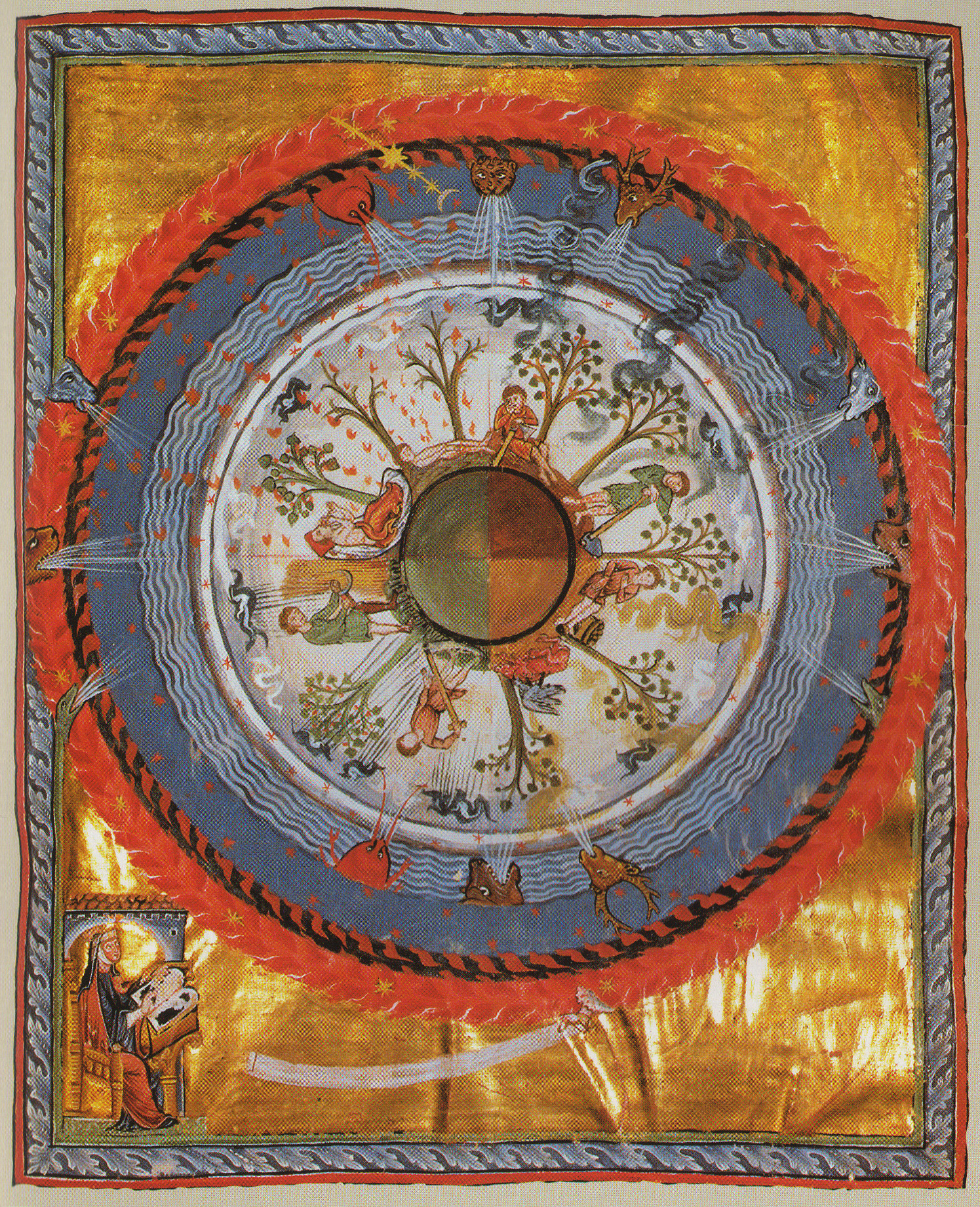

We can then understand that the appetitive part of the soul inclines toward the good, both sensible and rational, and attachment binds us to particular goods, persons, or aims. True virtue orders appetite and attachment toward the ultimate good, God, and thereby participates in flourishing. We cannot forget that God revealed Himself in a personal and historical way that adequately expressed His innermost mystery in the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ.

This same Christ entrusted His mysteries to a living organism, called the Church, which consists of a divinely instituted hierarchy that bears authority from God in teaching on matters of faith and morals, and a laity whose purpose is to continue the mission of Christ toward all the ends of the earth until His second coming. When these dimensions are misordered (or forgotten), the result is politics that caters to appetite (what we want) or attachment (what we feel bound to, perhaps out of fear, comfort, or proximity) rather than to the “real” as expressed in persons and community in light of the transcendentals and revelation. R.R. Reno has called such a politics “the return of the strong gods,” which is a phrase he uses to describe the powerful binding ideals, beliefs, and loves that give meaning and cohesion to a culture or civilization.

Amidst the collapse of belief in the weak gods of pluralism, openness, tolerance, inclusion, progress, and procedural neutrality, we see that society wants a return of stronger, more familiar drink. We see then a mix of more or less coherent clamoring for things like truth, God, patriotism, family, justice, blood, soil, and ancestry. As a result of the throwaway culture and the post liberal consensus’s attempt to alienate man from the pre-liberal past to avoid nationalism’s and populism’s revenge, we, ironically, see the world inclining itself once more toward these political expressions, not necessarily from a love of their more recent disastrous expressions but from a rejection of the disastrous results of liberalism.