The crisis of American political life is not merely a dispute about policies, parties, or power. It is a metaphysical and spiritual disorientation. It is a dislocation of identity and unity that cannot be resolved by electoral maneuvering, cultural nostalgia, or technocratic policy alone. At its core lie two competing visions of political unity:

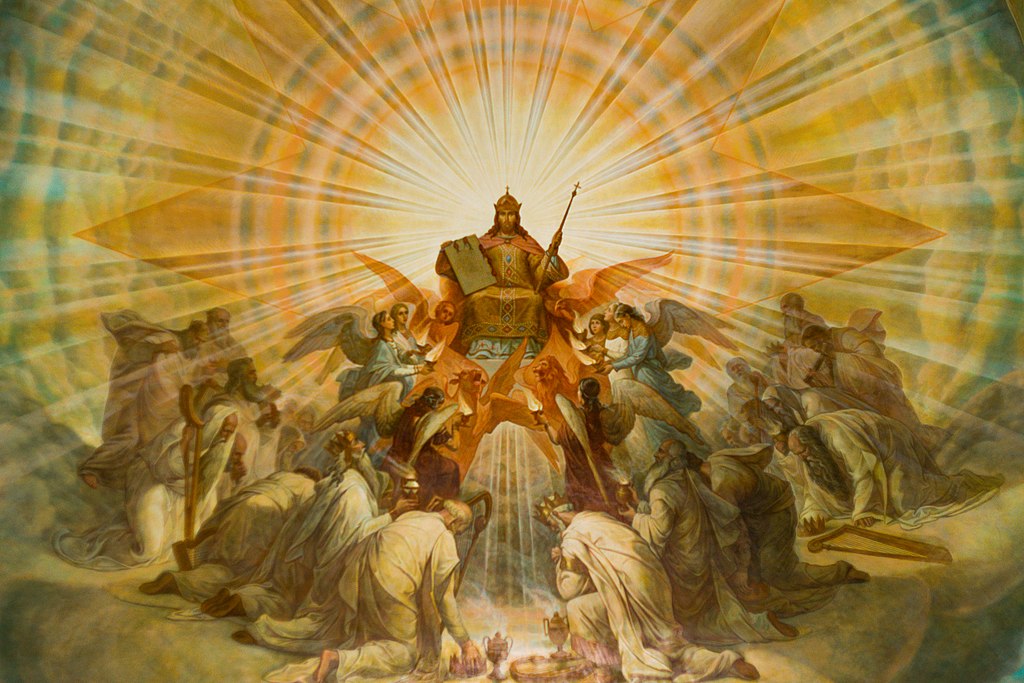

Unity understood as homogenization, dominance, or exclusion, characteristic of both secular technocracy and aggressive modern nationalism; and Unity understood as communio (a unity-in-difference grounded in shared participation in the truth), a posture that first and foremost acknowledges the Kingship of Christ and the authority of the Church.

Or, as Augustine once put it, the City of Man and the City of God.

To recover a truly Christian political vision for the United States that is simultaneously “one nation under God” but also a polity composed of enduring regional cultures and identities we must reflect on the deeper theological ground of unity and difference. This task involves neither political quietism nor uncritical patriotism, but the Christian praxis of faithful engagement with the world through the lens of nature and grace.

I. Nationhood as a Theological Reality: People and Culture in Christian Theology

The Church’s social doctrine consistently affirms that both the family and the people (or nation) are natural societies — ordered toward the flourishing of persons, culture, and common life. Pope St. John Paul II taught that a person “lives according to a culture which is his own” and that through language, history, and shared practices human beings become more fully themselves. Indeed, “Man always lives according to a culture which is his own…Culture is that by which man as man becomes more man, ‘is’ more, has more access to ‘being’” (Address to UNESCO, June 2, 1980, 6-7)

The New Polity reflection, Is Christianity Nationalist?, highlights that a “people” is not an abstract aggregate but a bearer of culture, a concrete historical community through which persons encounter the Divine and are drawn deeper into truth. The universal Church becomes more fully herself precisely through the diversity of particular churches and peoples, each offering a distinct way of incarnating the Gospel in its culture.

This insight is deeply consonant with Vladimir Soloviev’s metaphysics of union without absorption: diversity does not dissipate unity, but participates in a richer unity under Christ. Soloviev describes the Church as a communion where particular identities are not erased but fulfilled — each giving expression to the truth without closing the horizon of transcendence. Christ is not a tribal idol. He is the universal Lord whose reign embraces real cultural diversity precisely as diversity. This Christian vision of unity is not uniformity; it is complementary particularities ordered to common truth.

Such unity is not found in the modern nation-state’s drive for homogenization or external sovereignty. Modern nationalism was historically constituted through the consolidation of power which often involved the subordination of smaller, organic social forms and the imposition of a single civic narrative. In a word, the destruction of subsidiarity in favor of a more externally powerful sovereignty. The Christian vision, by contrast, does not make the state the ultimate horizon of belonging. It foregrounds the Church and the reign of Christ as the true source of political meaning. These realities of Our Blessed Lord and His Body truly reign, and yet, they do not destroy or disorderly subordinate power inappropriately as does the coercive nation-state.

II. Trinitarian Unity-in-Difference and American Particularity

D. C. Schindler and theological proponents of unity-in difference draw on the pattern of the Trinity (one God in three Persons) as the analogue for human community. The divine Persons are distinct yet perfectly united, each giving and receiving love without ceasing to be who they are. That relational pattern mirrors what a political unity ordered by grace would look like: a unity that affirmatively embraces difference rather than reducing it to sameness.

In American history, this paradox of unity under God alongside multiple enduring cultures is palpable. Colin Woodard’s American Nations thesis identifies distinct regional cultures in North America that have persisted through centuries: Yankeedom, New Netherland, Tidewater, Greater Appalachia, Deep South, El Norte, the Midlands, New France, Far West, Left Coast, and, of course, First Nation. Each of these regions reflects a distinct set of historical memories, values, and social priorities. They are not merely political subdivisions but cultural realities that shape political imaginations. To speak of America’s unity without reckoning with these cultures is to mistake uniform administration for true social communion.

From a Christian perspective, these regional identities are not enemies of unity, but signs of the analogical pluralism inherent in creation: the same divine truth can be incarnated in different historical forms without losing its universality. In fact, it would be absurd to think a country the size of the US was truly a mono culture. God did not create humanity as a monolithic mass. He created us as diverse images of Himself, called to communion in Christ. Even the primordial society, man and women, are an image of such diversity-in-unity. In this sense, the American political experiment of “one nation under God” comprised of distinctive sub-cultures can be seen as a political analogon of the Church’s own catholicity: one Body, many members, each with gifts that contribute to the flourishing of the whole.

III. The Kingship of Christ and the Church’s Political Role

The locus of Christian political unity is not a triumphant earthly empire, nor is it an abstract universalism that erases particularity. I hate love to disappoint many political theorists and thinkers. Rather, it is the Kingship of Christ over hearts and societies, mediated through the Church’s sacramental life and moral teaching. This kingship is not a blueprint for a theocratic state that suppresses difference; it is a normative horizon toward which politics must be ordered.

This christological principle clarifies much in the political confusion of our current moment. It resists idolatrous nationalism: the elevation of the nation or state to a quasi-divine status. A Christian political vision must place allegiance to Christ over, before, and through all civic attachments. It affirms the legitimacy of national and regional identities as real social forms, precisely because they are natural and can serve the human good when ordered by reason and charity. It insists that the Church’s political role is not to seize all temporal power for itself, but to accompany humanity’s pilgrimage toward truth, justice, and peace which includes prudential engagement in civic life without reducing the Gospel to a party manifesto.

Soloviev’s thought can be of great help here: political unity that truly reflects Christ’s Kingship is neither assimilation nor isolation. It is a universal embrace that respects particular integrity. The Church’s mission is thus to purify and elevate national identities, even the sub nations of the one nation under God, not to destroy them, not to fossilize them, but to anchor them in the gospel’s gravitational pull upwards. In this way we can have a political theory rooted in a theological reality that affirms what has always been in America’s bones (or intentions) of united states. Not a super-federal government that dresses slightly different every hundred miles.

IV. Unity-in-Difference as a Political Imperative

What then unites America politically? Not uniformity of opinion, not a single culture, not a political idol. What unites and what should unite is the common good as a participation in the divine order of the cosmos. There are natural sources of unity out of political need and reality, and then their are the supernatural possibilities of a unity that can truly make each American into brothers and sisters: the Eucharist. To use the language of Catholic social teaching, unity is realized through:

Shared participation in truth and dignity — each person, each regional identity, each state must be recognized as bearing human dignity ordered toward God.

Subsidiarity and fraternity— local cultures should be preserved and allowed to shape political life, while larger political communities facilitate the coordination of common goods without crushing local particularities.

Open horizons of identity — borders and local character should be horizons, not walls, through which encounter with neighbors of other cultures can occur without fear or erasure.

Political ordering toward justice and charity — laws and policies must protect the vulnerable, honor the natural institution of the family, encourage real economic participation, and cultivate virtues necessary for free and responsible citizenship.

Christian political unity comes not from coercive conformity but from those practices and institutions which foster a people’s capacity to seek truth together and to embrace difference without contempt. This mirrors the Trinitarian logic of unity and distinction: one body of many members, none dispensable, all contributing to the flourishing of the whole.

Conclusion: A Politics of Communion, Not Conquest

The United States, as “one nation under God,” has never been (and will never be) a perfect realization of unity. Nor is it meant to be the pure incarnation of Christ’s kingdom, for that kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36). But it can be a site of political communion, a space in which the divine truth resonates through many voices, many histories, and many identities.

A Christian politics for America must therefore be neither xenophobic nationalism nor rootless universalism. It must be a politics of communion understood as a unity-in difference that accepts the reality of enduring regional cultures while holding them accountable to the common good as illuminated by Christ’s Kingship and the Church’s teaching. Only then can America’s particular story participate, even imperfectly, in the wider story of salvation history, where every tribe, tongue, and nation finds its place in the harmony of the Body of Christ.